Myopia control

20/11/2019

Defining pre-myopia: a new term for an age-old condition

Leonardo da Vinci’s musings on the eye included the idea of a contact lens

Over two millennia ago, Aristotle (350BC) first coined the term myopia. He was likely describing the “closed eye” appearance of those squinting as a means to overcome their characteristically impaired distance vision.

Myopia has recently taken centre stage as a priority for clinicians, scientists and the ophthalmic industry due to the significant public health concerns and commercial opportunities arising from the global myopia pandemic. However, detailed scientific scrutiny of myopia is not such a recent phenomenon, with efforts to explore the aetiology and complications of myopia extending back to Renaissance times.

The International Myopia Institute (IMI) has recently sought to address the terminology problem by publishing a simplified and standardised definition and classification system based on qualitative and quantitative criteria

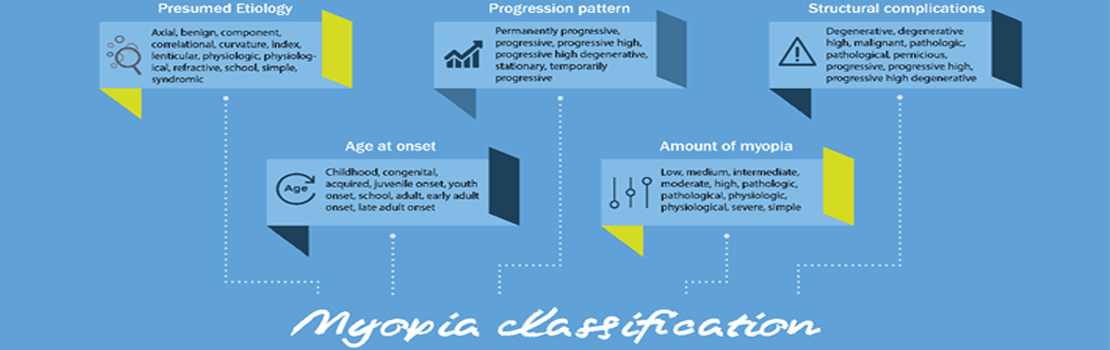

One of the consequences of such efforts to better understand myopia has been the introduction of a diverse and bewildering array of terminology describing the condition (see figure below). The International Myopia Institute (IMI) has recently sought to address the terminology problem by publishing a simplified and standardised definition and classification system based on qualitative and quantitative criteria. (1) The most interesting aspect of this paper is, perhaps, the introduction of a definition for “pre-myopia”.

Descriptive Terms Used to Describe Various Subtypes of Myopia (Adapted from Flitcroft et al.).(1)

The Definition

As clinicians, we’ve probably been in the situation of examining a young child and informing the parent that s/he is ok for now and doesn’t need glasses…yet, although, we know they will soon. The child who is slightly hyperopic or emmetropic, but just a little too early in their development – these are the pre-myopes.

In this paper led by Prof. Ian Flitcroft, the IMI have put a formal definition on pre-myopia as a “non-myopic refraction in which a combination of risk factors (e.g. young age, parental history) and the observed pattern of eye growth indicate a high risk of progression to myopia.”

Pre-myopia is of considerable interest for one specific reason, the possibility to identify pre-myopes at risk of myopia development as a target for preventive treatment. Lifestyle interventions such as increased time outdoors appear to be most effective before the onset of myopia. Additionally, treatments such as low dose atropine may provide the opportunity to delay or prevent myopia.

There is already some evidence to suggest this may be a successful strategy, with one study (published as far back as 2010) demonstrating that regular topical administration of 0.025% atropine eye drops can prevent myopia onset and reduce the rate of myopic shift in pre-myopic children.(2) A larger trial, the Pre-Myo Study, is now ongoing in Hong Kong and designed to explore the capacity of 0.01% and 0.05% atropine to prevent myopia onset, so this is very much an emerging field.

Evaluating myopia’s beginnings and present-day advancements and treatment, leads us to ask what lays ahead for generations to come. Might the future of optometric practice involve the active treatment of children to prevent refractive error rather than just managing the symptoms after it develops? Let’s hope so, as this might just provide the best opportunity to minimise the future public health consequences of the myopia pandemic.

References

1. Flitcroft DI, He M, Jonas JB, Jong M, Naidoo K, Ohno-Matsui K, Rahi J, Resnikoff S, Vitale S, Yannuzzi L; IMI – Defining and Classifying Myopia: A Proposed Set of Standards for Clinical and Epidemiologic Studies. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019;60(3):M20-M30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.18-25957

2. Fang PC, Chung M-Y, Yu H-J, Wu P-C. Prevention of Myopia Onset with 0.025% Atropine in Premyopic Children. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2010. 26(4). http://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2009.0135.